Welcome to the second article in our user experience series here at IQ Inc!

Welcome to the second article in our user experience series here at IQ Inc!

In our previous post, we laid the foundation for why user experience is important to both the user and the business. If you’d like to learn more about that or refresh your memory, please check out the previous post here: http://iq-inc.com/why-ux-is-important. We also briefly mentioned the topic of user research which we will explore in this article.

The first step to great design is to first understand your users, their needs, desires, constraints, and environment. Without this crucial first step, any subsequent ideation sessions are just speculation about how to design the product.

If we can leave anything with you today, it is this: you are not the user.

You may think you know how they behave and what they want to see, but experience shows that more often than not, what we think the user wants and what the data actually shows can be surprisingly different. That being said, user research is about generating the data and findings to back up design decisions.

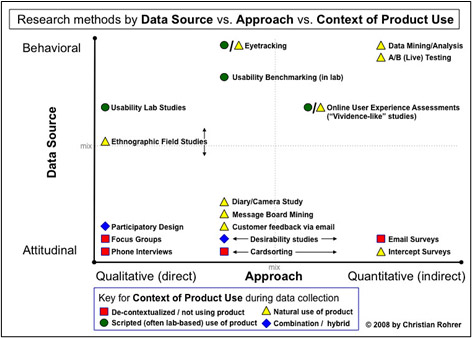

The graph below organizes some of the various methodologies used to conduct user research. Ideally, a mixture of several of these techniques can be applied. Here at IQ Inc., we’ve employed some of these methodologies in our projects as well. The following paragraphs will detail some of our processes and lessons learned from our experiences.

When we are conducting user research, there can be tension between field studies or laboratory studies. Do we observe the user in their natural environment and be subject to possible external factors affecting our metrics, or do we bring the user into a lab environment where the variables can be better controlled but may skew or bias the data?

A benefit to conducting user research in the field is that a designer or developer can observe external actions (actions not taken within the system) that may have an impact on usability. In one particular project, we observed that a user may be on the phone with an authorizing party who would tell them that a certain change was okay, yet would be prevented from making the change because of the overly restrictive rules of the software. Therefore, we concluded that the software must prevent the user from causing real issues but also allow them to override those rules when necessary. This realization only came by observing how our users behaved in their day-to-day work.

In another project, we interviewed several current users of a product and applied a methodology called contextual inquiry. We first performed a semi-structured interview about how they currently use the product and observed them performing some basic tasks. We wanted to allow for the user to work through a specific set of tasks while only observing and taking notes. By allowing the user to forget we were there, we could gain valuable insight into how they were currently using the system. Too many stops or interruptions for questions could have influenced their behavior. After the initial set of tasks, we then asked the users to perform the same tasks again while stopping to ask questions at various points based off of notes from the initial observation (e.g. Why did you click this button, Why did you open up another text file during this step?).

When scheduling a session with a user participant, it is beneficial to record the interview or observation session in some way. Having a recording can allow researchers to revisit the session from a different perspective and formulate follow-up questions or points of interest for further discussion.

Finally, when asking questions during a research session, avoid yes or no questions when possible. Asking these sorts of questions typically indicates that a researcher already has an answer in mind and that answer can limit discussion. Instead, try to focus on open-ended questions to better understand the needs of the users who are interacting with the product. For example, asking, “do you wish you could load the file with one click?” is a leading question and a positive reply is ultimately meaningless because it does not give any insight into the user’s needs and desires for this particular interaction. A better question would be: “I see it took you a long time to load the file you wanted. What could make this process easier for you?” This opens up a discussion and allows you to gain more valuable insight into how the user interacts with the system.

Thank you all for reading this far. By now, you should be aware of the importance of user research and have learned some methodologies and tips about how we apply them at IQ, Inc. Always remember that despite how tempting the desire may feel to simply assume how users behave and think, you are not the user.

If you want to continue learning about user research methodologies, take a look at the reading list below:

- https://www.usability.gov/what-and-why/user-research.html

- http://guidetouxr.com

- Don’t Make Me Think by Steve Krug

Authors: Sam Cheng and Scott VanKirk